The Impact of Official Discourse on Women’s Narratives of Iran-Iraq War

Abstract:

This article is an extract of a research with the same title which examines how women’s narratives of Iran-Iraq war are affected by official discourse of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The main hypothesis of this study is that women, in their narratives of this war, are unconsciously influenced by the official discourse of the society. In fact, women’s knowledge about war has been shaped by the structure of the official discourse of the society. Theoretical frame work of this article is based on Norman Fairclough’s theory on critical discourse analysis. First, I discuss the main concepts of Fairclough’s theory and then, in a chapter on the theoretically based methodology, I extract concepts for my empirical analysis. Applying this method, I analyze parts of four women’s memories of war, which have been published between (1980) and (2007). As a result, many propositions of the official discourse of the Islamic Republic – stemming, in turn, from informal and religious discourse of Iran – are detected.

Key words: Discourse, official discourse, narration, memory, critical discourse analysis

1. Introduction

War is one of the most complicated concepts with a long series of possible definitions. Due to the variety of sociological, psychological, political, and military approaches to war, it seems difficult to come to one certain definition of war. However, no matter how we define this phenomenon, it seems to posses all characteristics of a living creature. It grows and gets transformed from one mode to another. War is, despite the common belief, not at all a phenomenon with a definitive finale. Although it may come to an end physically, the society keeps on interacting with its symbolic entity.

Twenty months after Iran’s revolution of 1979, this country got involved in an eight-year war as its Western neighbor Iraq invaded its territory. The casualties of this war as well as its financial, social, cultural, and psychological consequences deeply affected the people who were involved in it.

Since the (physical) end of this war, we have been facing different “pathological” analyses of its consequences. Considering the fact, that this war has already become history, two points can be deduced. Firstly, every generation in any era looks at the past from its own point of view, thus reconstructing its history according to the situation it is living in. In other words, this interpretation is the result of the formation of a new historical view of the past. Secondly, one characteristic of major historical events is their ability to respond to the needs and requirements of different eras. It is this capability that makes an historical event eternal. This characteristic stems rather from the nature of an event than from propaganda. (Sheikh, 1984)

Provided we regard narration as present history allowing us to express our understanding of the past, it is the actors of narration –the actors of discursive action – who, via different narratives, express their relation to an historical event apparently lying in the past.Narratives of war express the way, in which its actors/participants perceive it from their own point of view. But how does the present history of war appear in narratives of war? And how is our knowledge of the war shaped through such narratives?’’

Each actor has his or her own narrative of a phenomenon. Thus, there are as many narratives of an event as there are people who have witnessed it. Nevertheless, while the narrators might regard their narratives of an event as unique, one can often find some common features in these reconstructed stories. In fact, narratives are influenced by a process of ideological norms based on the official discourse – a process that is naturalized.

Now the question is how this process appears so natural and unconscious. Since, the main sources of ideological propositions in a “language community” are men, and it is the male actors who define the ideological norms and relate them to the official discourse of a society, this study attempts to find out the propositions of the (patriarchal) official discourse in Iran, which shape women’s narratives of the war. Moreover, this study attempts to find a meaningful relationship between social action, discursive action, and text in women’s narratives of war. The essential notion is that “there is a fundamental relationship between specific characteristics of the texts, the way they are interconnected, and the nature of social action” (Fairclough, 2000). This is also assumed for women’s memories of war and the way they narrate it.

Women’s narratives of war illustrate their images of self/other as well as of war. The way they narrate war stems also from their knowledge of war. Since there has been a procedure to form women’s identity and knowledge of war by their narratives, why does the procedure of naturalization of women’s narratives appear so unconscious? The narratives chosen for this study are women’s memories of war. In a research with the same title, the memories of four women of war have been analyzed by applying critical discourse analysis after Norman Fairclough. Due to the limitations of this article, we only refer to parts of one of these memories.

2. The underlying theoretical framework

2.1 Theoretical concepts in Norman Fairclough’s notions

2.1.1 Discourse:

Discourse is one of the most important and constituting concepts of political, social and philosophical thinking of the west in the second half of twentieth century. Although this concept has been very often used in the social philosophy literature of medieval age and especially in modern era and can be found in the works of Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Rousseau, in recent decades contemporary thinkers such as Emile Benveniste, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida have used this concept in a new sense. This conceptual shift is so radical that in the last three decades Western scholars, when using this concept, specify that they are using it in its Foucaultian or post-structuralist sense (Salimi, 2004: 50)

Fairclough believes that discourse “is formed by some structures, but it also forms those structures and plays a role in reproducing and changing them. These structures are of a direct and immediate discursive and ideological nature (like discourse orders, codes and their elements such as words or turn-taking norms in a dialogue). Indirectly, however, they include political and economic structures, market relations, gender-based relationships, and relations inside the government and civil society institutions such as education.” (2000: 96)

According to Foucault: “Where between objects, types of propositions, concepts, and thematic choices there exists an order, correlations, ‘positions in common space, a reciprocal functioning’, and linked transformations, then a regularity, a system of dispersion is located and a discursive formation identified’’ (Smart, 2006:49). Fairclough regards a discourse as an interwoven collection of three elements: social action, discursive action (production, distribution, and consumption of text) and text. Therefore, analyzing a discourse means to analyze all these three elements as well as the relationship between them. Thus, he assumes a significant relationship between features of texts, the ways they are interconnected and interpreted, and the nature of social action.

In this short analysis of discourse we have encountered the following three main dimensions:

A - The application of language

B – Relating the beliefs (knowledge)

C – Interaction in social situations

2.1.2 Ideology

According to Fairclough, naturalization and non-transparency of ideology are among the essential characteristics of a discourse. He emphasizes that the non-transparency of ideology is part of its nature. Ideologies are not the same as beliefs or worldviews. They rather imply representations of the world according to specific interests. Ideologies create subjects which do not look like being created and conditioned, but seem to be free, alike, and responsible for their own actions. Ideologies pass the border of situational types and institutions. We should be able to explain how ideologies go beyond specific codes or a specific discourse (one example would be the metaphors that present a nation as a family) and how they relate these things via production and reproduction of relationships (ibid: 99).

The main question about ideology is what features and levels of language and discourse could become ideological. It is usually claimed that it is the “meaning” or the “content” – as contrasted against the “form” – that becomes ideological. These meanings are often considered as word meanings. Word meanings are no doubt important. However, other aspects of meaning like implications, presuppositions, metaphors, and coherence, are significant as well. For instance, interpreters come to coherent understanding of a text based on the clues and allusions in the text or by using other sources (such as internalized ideological and discursive structures).

Coherence is an essential factor in ideologicla production and reproduction of issues in a discourse. A text takes only a subject as its cornerstone that “can” automatically interrelate seemingly unrelated, potential elements of the text to make sense of them. In fact, by doing so, texts contribute to the creation of their subjects. However, an opposition between form and content is misleading. In fact, formal features of the text might be ideologically vested too; even aspects of the style might be ideologically meaningful (ibid:100).

Ideological formation

Ideological formation refers to different ideological stances, which are related to different forces inside an institution. The variety of ideological formations is a pre-condition for, as well as a result of, conflict between different forces inside the institutions. In other words, conflict between forces creates ideological barriers between them, and ideological struggle is part of this conflict. This institutional conflict is related to class conflicts, even if not necessarily in a direct and transparent manner, and the ideological and discursive control of the institutions is itself a subject of the class conflicts (ibid, 47).

Formations’ associated with different groups within the institution. There is usually one ideological-discursive formation which is clearly dominant. Each ideological-discursive formation is a sort of ‘speech community’ with its own discourse norms but also, embedded within and symbolized by the latter, its own ‘ideological norms’. Institutional subjects are constructed, in accordance with the norms of an ideological-discursive formation, in subject positions whose ideological According to Fairclough social institutions contain “diverse ‘ideological-discursive underpinnings they may be unaware of. A characteristic of a dominant ideological-discursive formation is the capacity to ‘naturalize’ ideologies, i.e. to win acceptance for them as non-ideological ‘common sense’” (ibid, 23).

2.1.4 Ideological Naturalization

Naturalization turns the ideological representation into common sense and makes them non-transparent – they are no longer looked at as ideology. These effects can be explained in two ways: a) By the process of construction of subjects, and b) by the concept ideological-discursive formation. Thus, subjects are typically unaware of the ideological dimensions of the subject positions they occupy. This means that they are not committed, in any acceptable way, to the relevant ideological dimensions. Sometimes, a person – a social subject – may either occupy some contradictory institutional positions or occupy a position that does not match his/her beliefs or social relationships without being aware of such contradictions (ibid, 51-5).

Fairclough is of the opinion that:

A- Ideology and ideological actions may, more or less, disconnect from their social origin, namely from personal interests that have created them. In other words, they may become more or less naturalized. As a result, they are not looked at as being created by the interests of social groups, but rather as common sense – as the “nature” of people and objects.

B- Thereby, ideologies and naturalized actions are turned into “background knowledge” and get activated in communication. So, the orderliness of interactions depends in part upon such naturalized ideologies.

C- Thus, the orderliness of interactions as a micro and local incident will depend on a higher order, namely on agreement upon ideological actions (ibid, 38).

2.1.5 Ideological norms

“In order to construct a subject, the learning of ‘prescriptive ways’ of speaking –attributed to a subject position – should be accompanied by the learning of the corresponding ‘ways of looking’ (ideological norms)”. Fairclough emphasizes this notion because, in his opinion, a collection of discourse norms “necessarily encompass specific background knowledge. Since this concept has an ideological element, one can learn both ideological norms simultaneously” (ibid, 50). Then he adds: “Institutions as ideological-discursive orders possess alternative collections of ideological-discursive norms too. Moreover, each institutional frame includes formulation and symbolization of specific collection of ideological representations. In other words, specific ways of talking are based on specific ‘ways of seeing’ ” (ibid, 45-47).

2.1.6 Social institutions

It was said that social institution can be called a kind of speech community and (in a broader sense) an ideological community. Then we can claim that institutions construct subjects ideologically. In fact, institutions give the appearance of having such specifications – but it is only the case when an ideological-discursive formation is clearly dominant. Fairclough believes that these properties can be attributed to ideological-discursive formation, not to the social institutions, because this is ideological-discursive formation that relates subjects to its collections. These collections include speech events, participants, settings, topics, goals and, simultaneously, ideological representations. According to Fairclough: “Ideological-discursive formations are arranged according to their levels of dominance. In a social institution there are usually only one dominant ideological-discursive formation and some dominated ones.’’ (ibid, 48-49). There are three levels of social phenomenon: 1 – Social formation, 2 – social institution, 3 – social action.

One can look at the relationship between the three levels of social phenomenon (social formation, social institution, and social action) in a top-down manner so that social formation determines social institutions, and social institutions determine social actions. From one hand, we should say that this is an essential attitude, from another hand, it is considered insufficient since it is too mechanical and non-dialectic because it does not let it to be bottom-up (ibid, 43). where an IDF has undisputed dominance in an institution, its norms tend to be seen as highly naturalized, and as norms of the institution itself .

2.1.7 Background information

The concept of “Background knowledge” turns different aspects of the material that underlies the interaction, such as beliefs, values, and ideologies, into knowledge. Knowledge refers to the facts that are to be known, facts that are coded in propositions directly and transparently related to them. When an ideological-discursive formation dominates in an institution, its norms tend to be regarded as deeply naturalized – as the norms of the institution itself. Therefore, a specific ideological representation of a reality looks merely as a transparent reflection of that reality equally delivered to everybody. Thus, ideology creates reality as an effect. The unclear concept of background knowledge reproduces, completes, and reflects this ideological effect, because it looks at such “realities” as objects of knowledge. According to Fairclough the concept of background knowledge plays also a role in the reproduction of another effect: “independent subject” as a specific appearance of the general inclination towards non-transparency – a tendency which Fairclough considers as being inherent to ideology (ibid, 53,54).

2.1.8 Hegemony

Hegemony is the dominance of one economic class, united with other social forces, over the whole society. This dominance is always incomplete and temporary and similar to unstable equilibrium. Instead of merely ruling over lower class, hegemony prefers to satisfy them by using ideological tools and giving them some incentives for integration.

The ideological dimensions of hegemonic struggle can be analyzed by applying Fairclough’s notion of discourse treated in the last sections. The discourse order forms the ideological-discursive aspect of a contradiction or unstable equilibrium. You see what was previously said about the discourse order as a heterogeneous and contradictory knot conforms to the concept of “ideological knot”. Discursive action is an aspect of a struggle which contributes – to different degrees – to the reproduction or change of the present discourse order, and consequently contributes to the reproduction or change of the present social and power relationships.

In most kinds of discourse, the main actors are not social classes (or political forces related to social classes or fronts), but rather interacting social groups like teachers-students, lawyers- clients, police-people, and men-women. Hegemony is a social process (at macro level), while most of the discourses are local by nature, and happen within or around specific institutions like such as family, school, neighbors, workshops, and courts. Hegemony also provides a mould. The success of hegemony in society requires, to a certain degree, uniformity of semi-independent local institutions in such a way that the power relationships are formed to some extent by hegemonic relationships.

This notion leads us to another issue: the links and relationships between the institutions as well as the links and mobility among institutional discourse orders. Achieving unity and uniformity deserves due attention, even though this might appear as a difficult task. However, such an end should not be striven for at the cost of underestimating the independence and relative uniformity of non-class struggles such as conflicts between ethnic groups, gender conflict, and other issues concerning the institutional agency (ibid, 103,105).

2.2. Norman Fairclough’ critical discourse analysis

2.2.1 Discourse analysis with critical objectives

Discourse analysis is the study of the ways texts are constructed, their functions in various fields, and their internal contradictions. This approach stems from different sources such as theory of verbal action by Austin, constructivism and post-constructivism, hermeneutics, critical theory, and Foucault’s theories.

Critical discourse elevates the level of discourse analysis. Due to the works of great thinkers like Jacques Derrida, Michel Pecheux, Michel Foucault, and especially thanks to the direct contributions of Teun van Dijk and Norman Fairclough, discourse analysis has – in a much broader scope than social linguistics and critical linguistics – entered social, cultural and political studies, assuming thereby a critical stance. The intellectual foundations of discourse analysis go beyond text or speech analysis. Discourse analysis is based on the following presumptions:

1- The same text can be interpreted in many different ways. 2. Reading a text is always a wrong reading. 3- Text has a whole meaning which does not necessarily lie inside the text. 4- Texts are ideological. 5- Truth is always in danger. 6- Every text is produced in a specific situation; therefore its social context is of major significance (Bahrampoor, 1999).

Fairclough differentiates in his discourse analysis between critical and descriptive objectives. “Firstly, the order of interactions depends on the assumed ‘background knowledge’. Secondly, background knowledge consists of ‘naturalized’ ideological representations that gradually look like non-ideological ‘common-sense’. Pursuing critical objectives means to try to clarify this naturalization. In a broader sense, it means to disclose the social determinants and effects of discourse which are essentially hidden to its participants. ‘Descriptive’ discourse analysis, which currently dominates the research on discourse, is devoid of these considerations. The theoretical premise of critical approach is based on the notion that micro events (such as discourse) are related to macro structures in a way that the latter are the conditions of the former as well as their results. Therefore, the critical approach does not accept any rigid and precise border between micro and macro studies” (ibid, 26, 27).

However, exactly such a separation of micro and macro has been practiced in the most part of the predominantly descriptive works on discourse (verbal interactions). Thus, pursuing critical objectives means primarily to study verbal interactions by considering their determination by, and their effects on, social structure. Anyhow, as it was earlier, in the section on text, mentioned, the participants of interaction are neither aware of its determinants nor of its effects. Lack of clarity is the other side of the coin of naturalization. Therefore, the objective of critical discourse analysis is denaturalization (ibid,40).

In his critical discourse analysis, Fairclough looks for a precise text analysis as an important tool of scientific study of social and cultural actions and processes. Moreover, his critical discourse analysis is not simply another form of academic analysis, but also an approach which can be applied in linguistic-discursive studies of domination and exploitation. Every body should participate in creation and expansion of critical awareness about language as a parameter of domination. And it should be emphasized that discourse analysis of oral or written texts should be congruent with organized analysis of social structure.

2.2.2 Levels of discourse critical analysis

2.2.2.1 Descriptive level

Descriptive approach, either gives us quasi explanations about interaction norms like the pattern of ‘activity goal, or looks at interaction norms in such a way as if they would only need description, not explanation. In either case, assuming that the ability of preserving dominance of ideological-discursive formation is the greatest effect of power (structure) on discourse, ignoring norm explanation causes ignoring the power. Moreover, the strong emphasis (of descriptive analysis) on participatory dialogue between ‘equal people’ has even led to a neglecting of the questions regarding social positions.

According to Fairclough: “Descriptive approach upgrades ‘equal people’s participatory dialogue’ to the level of ideal verbal communication (ibid, 58). From critical point of view, describing the conditions in which special kind of interactions may happen is an essential element in explaining this kind of interactions. However, Fairclough is of the opinion that we can not attain these descriptions unless we consider the distribution of power and the way it is exerted in the institution and thereby in a social formation. Given limited explanatory objectives in descriptive approach, the concept of power is left outside the realm of this approach. Fairclough believes that description as a stage in critical discourse analysis has the function of exploring formal features of a text.

The concept of ideology is not congruent with limited explanatory goals in descriptive approach, because ideologies as representations created by social forces lead us beyond the immediate situation and links us to social institution and social formation (Fairclough, 2000, 54,55).

2.2.2.2 Interpretation

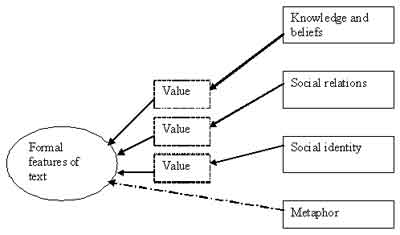

1. Formal properties of texts are of experiential, relational, and expressive value or a combination of them and Fairclough relates these aspects to three aspects of social practice which might be constrained by power (contents, relationships, and subjects) and their structural impact (on knowledge and beliefs, social relationships, and social identities). Anyhow, it is clear that we cannot directly understand the structural effects on society by analyzing formal features of texts, simply because the relationship between text and social structure is an indirect one. This relationship is primarily established by discourse, part of which is the text, because the value of textual features gets real and socially operative only in social interactions. It is through this venue that the texts are produced and interpreted against the presuppositions of common-sense (part of background knowledge) which, in turn, renders the text features their values. This leads us to the second stage of our work: interpretation. Fairclough has used the word ‘interpretation’ as the name of one stage of the procedure (of analysis) as well as for interpreting the text by discourse participants. He has chosen this word to emphasize the similarities between discourse participants and discourse analysts.

The interpretations are a combination of the content of text and interpreter’s mind. By ‘interpreter’s mind’, Fairclough means interpreter’s background knowledge which is used to interpret the text. From interpreter’s point of view, the formal features of the text are considered as clues which activate certain elements of background knowledge in the interpreter’s mind. Interpretation is the product of dialectical relationships between these clues and background knowledge in the interpreter’s mind.

Discourse participants interpret the situational context partly by external clues (the objective features of the situation, and personal characteristics of the participants) and partly by using some aspects of their own background knowledge. These aspects are then used for interpreting the clues especially regarding social and institutional representations of the social order which enable the participants to relate their situations to certain kinds of discursive situations. The interpretation of situation by discourse participants determines the kind of discourse being applied. This, in turn, will affect the styles of interpretation. For instance, the interpreters might have some speculations about the structure of the text and its main idea, which may be helpful in understanding the meaning of fragmented phrases and achieving some coherence between them. In other words, texts should be interpreted in both top-down and bottom-up style.

This is also the case with the relationship between the interpretation of text and that of context: On the one hand, when an interpreter determines the context, this will affect his interpretation of the text. On the other hand, the context interpretation depends on text interpretation and may change during the interpretation. Thus, the picture being constructed in our mind by the interpretation is a sophisticated one (ibid, 221).

It is necessary to clarify the participants’ situation of concern, and their common interpretation in each case. We should also be aware that one participant’s stronger interpretation may be imposed on the other. Another consequence is that ideologies and their fundamental power relationships have profound impact on discourse production and interpretation, because they have been located in interpretation styles-social orders- which are the corn stone of the highest level of interpretation on which other cases rely-‘ which situation am I in’. Therefore, the interpreter has the structure of the text in mind. It means that the values of specialties of the text depend on the interpreter’s diagnosis of the text,(ibid,230).

It is necessary to explain, in any specific case, the situational context of discourse participants and their common as well as individual interpretations. We should also beware of the way a powerful interpretation of one party could be imposed on the other parties. We should further consider the fact that ideologies and the power relations related to them have a deep and extensive impact on the interpretation and production of discourse, simply because they lie in the interpretation procedures - the social orders - which underlie the highest level of interpretative decision on which others are dependent – what situation am I in?

The consequences of this utter dependence of interpretation on situational context are a kind of warning to linguists who habitually consider meaning as a mere linguistic issue. The understandable reaction would be to try to define the borders of the context and to confine its range. Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that the situational context of each discourse encompasses the highest level of social system and power relations. As, traditionally, it is believed that each sentence implies the whole language, discourse implies the whole society. This is true because the fundamental classification patterns of social and discursive action which underlie other issues – what Fairclough calls social orders and discourse orders – will be formed by social and institutional moulds of that specific discourse.

The stage of interpretation corrects this false belief that subjects of a discourse are independent. In fact, this stage explicates what is implicit to the participants: dependence of discursive action on unexplained assumptions derived from common sense and included in the background knowledge and in the kind of discourse. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the stage of interpretation will not, on its own itself, explicate the power relations, domination, and ideologies which are built into the above-mentioned assumptions, and which turn the ordinary discourse practice into arenas of social struggle. To realize this objective, a stage of explanation will be required (ibid, 244).

2.2.2.3 Explanation

We can pass from the stage of interpretation to the stage of explanation by noting that by applying different aspects of background knowledge as interpretative procedures in production and interpretation of texts, this knowledge will be reproduced. This reproduction is for discourse participants an unconscious and unintended side-effect. This is also the case with production and interpretation. Reproduction connects the stages of interpretation and explanation, because while interpretation pays attention to applying background knowledge in discourse processing, explication deals with social constitution and change of background knowledge, including of course their reproduction in discourse practice. The aim of explanation is to describe discourse as part of a social process, as a social practice, by showing how social structures determine this discourse. It also shows what kind of reproductive effects discourse can have on those structures. These effects end up namely in protecting or changing those structures. Background knowledge is the mediator of these determinations and effects. This means that social structures shape background knowledge, which in turn shapes the discourses, and the latter sustain or change background knowledge, which in turn sustains or changes the structures (ibid, 245).

We can think of explanation as having two dimensions, depending on whether the emphasis is on the process (of struggle) or on the structure (of power relations). On the one hand, discourse can be seen as a part of social struggles, and can be placed in a broader context of these (non-discoursal) struggles and their effects on structures. This point of view puts the emphasis on the social effects of discourse, on creativity, and on future. On the other hand, it can be shown which power relations determine the discourses. We can also show that these relations stem from social struggles, and are produced by those in power (and – ideally - naturalized). This point of view puts the emphasis on the social determination of discourse and on the outcomes of previous struggles. Both social impact of discourse and social determination of discourse should be analyzed at three levels of social organization (societal, institutional, and situational).

Explanation includes an illustration of a special perspective of background knowledge as various ideologies. This means that assumptions about culture, social relations and social identities, which are part of background knowledge, are determined by power relations in society or in an institution. Regarding their role in sustaining or changing power relations, such assumptions are analyzed from ideological point of view (ibid, 250).

3. Combining theory and method to explain women’s memories of Iran-Iraq war

Concerning the topic of this article (The impact of the official discourse of Iran on women’s narratives of Iran-Iraq war), I will now try to explain different dimensions of this subject applying some concepts of critical discourse analysis after Norman Fairclough as well as the methods and objectives of this approach discussed in previous sections.

3.1. Official discourse; the discourse of Islamic republic of Iran

A discourse in the framework of the dominant political system has the objective of producing meaning in the official public. In Iran this discourse is crystallized in the official discourse of Islamic republic of Iran.

3.1.1 Items of official discourse of Islamic republic of Iran

3.1.1.1.1 Trying to export the Islamic revolution

3.1.1.1.2 Emphasis on Iranian soldiers’ rightfulness in defending the ideals of the Islamic revolution

3.1.1.1.3 Strong belief in holy war (jihad) and martyrdom for the ideals and values of the Islamic revolution

3.1.1.1.4 Emphasis on religious obligations as part of values of the Islamic revolution

3.1.1.1.5 Emphasis on avoiding any physical contacts between men and women who are na-mahram (men and women who are allowed to marry each other)

3.1.1.1.6 Emphasis on sexual segregation in social relations

3.1.1.1.7 Emphasis on hijab (covering) as one of the main norms of the Islamic revolution

A short review of these rules clearly shows that they can be observed both in the religious and Islamic revolution discourses

.

3.1.2. Reproduction of ideological propositions in women’s narratives of war

In reproduction of ideological propositions in women’s narratives of war, it is not the domain of proposition production, but their distribution and consumption, which is of primary interest. In fact, these propositions are reproduced by being unconsciously utilized by their users. To put it more clearly, in parts of women’s memories of Iran-Iraq war, these propositions have been used and reproduced by the narrators. Some of these reproduced propositions are as follows:

1- Keeping personal distance between a Moslem woman and a stranger man.

2- Reproducing the meaning of Moslem woman’s covering (Hijab).

3- Separating Moslem women who believe in Hijab and other religious instructions from the women who do not.

4- Trying to export the revolution.

5- Emphasizing on martyrdom as an ideological ideal.

All these propositions have been reproduced by using radical and different structures for referring directly to ideological beliefs stemming from official discourse of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

3.1.3 Ideological naturalization in women’s narratives of war

According to Fairclough’s theory, naturalization turns specific ideological representations – namely the ideological aspects that are used and reproduced by male discourse subjects – into common-sense and consensual principles, thereby making them opaque in such a way that they cannot be called ideology anymore. Concerning women’s narratives of war, reproduced ideological propositions are naturalized due to discursive action, social action and contexts of their memories (the pillars of female discourse) without their awareness of this naturalization process.

3.1.4 Hegemony reproduction in women’s narratives of war

It was previously noted that according to Fairclough, men are the source of production of ideological propositions in a speech community, and that ideological norms are usually determined by male actors and account for the main part of ideological norms of the official discourse in a society.

By analyzing parts of women’s narratives of war, I will show how these propositions dominate such narratives in a hegemonic framework and without the awareness of the narrators.

The course of action in these narratives reflects the repetition and reproduction of those propositions that represent the official discourse with its hegemonic characteristics as women’s common-sense. According to Fairclough: “Hegemony gives us a model and a mould” (2000, 104). Applying this definition of hegemony in the analysis of selected women’s memories of war implies that even without an intended exertion of domination by the formal discourse, a unity of certain groups and institutions with the government targets the independent thinking of human groups such as women, and pushes them towards internalizing the ideological norms which dominate the society.

3.2. Retrieving critical discourse analysis in women’s memories of war

3.2.1. Descriptive level

The first stage of my critical discourse analysis deals with women’s memories of Iran-Iraq war and the impact of official discourse on them. For this purpose, some memories of women in different social groups are selected. After extracting discourse propositions from some selected memories as the smallest units of narratives, I will deal with the meanings of these propositions and their dependence on, or independence from, official discourse of the Islamic Republic.

Memory 1:

“After the inspection of the Jeep, the Iraqi soldier came to me. I was scared a lot. Some breathtaking moments passed. I took a glance of beg at the soldier to change his mind. It did not work. I told him loudly: ‘Don’t you have any religion. Aren’t you Moslems?’

One of the soldiers said: ‘we should give you a body inspection.’ I said: ‘There are no pockets on my dress. Every thing is in the car. Make sure I don’t have any thing.’ The soldier went back. The commander said: ‘It’ll be clear when you are taken to some where else.’ They went to the car. I took a breath in relief and looked at Habib. He was pleased. I felt how hard these moments might have passed for him…” (Captive 0339,23)

Point 1:

Applying the theory of Norman Fairclough, first we concentrate on the formal features of the narrative such as experiential, relational, expressive, and metaphoric values.

1- Formal features of memory 1

1-1 Experiential values: Prohibition of na mahram men touching Moslem women’s

Body.

1.2. Relational values: Using formal language between “enemy” and captive woman.

1-3- Expressive values: Narrator’s negative evaluation of enemy’s ignoring of the Islamic code for gender relations.

2– Discursive propositions

2.1 – Keeping personal distance between a Moslem woman and a foreign man.

2.2. Avoiding sins.

2.3- Prohibition of Na mahram man touching a Moslem woman, even if she is a captive.

2.4- The belief in the rule that only mahram men can touch a woman.

2.5- Ideological aspect of this belief based on religious instructions

2.6- Reproduction of meaning of Hijab (covering all parts of the body) in the propositions of the Islamic revolution.

2.7- Separating religious women from non-religious ones.

2.8- Creating new behavior patterns to attract audience.

3-Semantic procedures

3.1.“I was scared”: Unintentional

3.2. „Breathtaking moments”: Unintentional

3-3- „A glance of beg and request’’: Unintentional

3-4- „I shouted: ‘Aren’t you Moslems?’ ”: Unintentional

3-5- „I said: ‘My dress does not have any pockets.’ “: Intentional

3-6- “I took a breath of relief.”: Unintentional

3-7- „Habib was pleased”: Intentional

3-8- „I felt how these moments…”: Unintentional

3-9- „Aren’t you Moslems…”: Intentional

Point 2:

Since it can be said that each discourse consists of propositions and semantic procedures to produce meaning, I will point to the meanings of the propositions and semantic procedures of the mentioned memory.

4 – The produced meaning of semantic procedures of the propositions of this memory

4.1. Emphasis on respecting religious relations of Moslem women and na mahram men.

4.2. Presenting a religious pattern for Moslem women to emphasize the importance of religious beliefs and practicing them even in hard situations like being a captive.

4-3- Referring to Hijab as a religious value in Islamic revolution discourse.

4-4- Making a model out of a religious meaning as a propaganda for Islamic revolution values.

4-5- Segregation model for Moslem men and women.

5. Discourse analysis

Among the produced meanings and their different resulted discourses, items 4-1 and 4-2 are placed respectively in religious discourse and Islamic revolution fields informal and formal. Items 4-4 and 4-5 are among requirements of formal Islamic republic discourse.

In the memory of an Iranian captive woman, there are different formalistic experimental and expressive specialties. The discourse statements are affected by formal and informal discourse of Islamic republic and Islamic revolution. This memory is the narrator’s formal and ideological instructions and beliefs. Although confirming mutual social relations with enemy and even narrator’s negative evaluation of enemy’s not being loyal to religious rules about men and women indicates communicative and expressive values of this memory, it seems to have emphasized social relations by excessive use of experimental values.

Interpretation level

The second stage of critical analysis of women’s memories of Iran-Iraq war deals with interpreting the texts to see why or how much they have been affected by official discourse of Islamic republic or other discourses. So, I have extracted the discourse statements of these statements in three levels as religious discourse, Islamic revolution discourse, and Islamic republic discourse.

Memory 2

The small lamp of the ambulance was turned on and reminded me the beginning of the night. Habib decided to say his prayers. One of the guards noticed him. He held his gun with his another hand and took out a Mohr from his pocket. Since he knew Habib was an stranger, he turned to me and said:’’ Take it, sister. It is from Karbala. I am also a Shiite like you. But, I am a soldier now. I have decided if I am ordered to kill an Iranian, I will first shoot at the one who has ordered me and then I will kill myself. I’d like to surrender myself to Iranian troop. (captive 0339,23)

Situation: Inside an ambulance, Habib is a captive, the soldier is the enemy. In this situation, every thing is in an interaction. Habib wants to say his prayers. The soldier gives him a Mohr( a piece of stone to one’s fore head while saying prayers). Then the soldier says the Mohr is from Karbala to show that he is Shiite. He also explains that he has to obey his commander. However, if he is ordered to kill a person, he will also kill himself. Religious discourse indexes such as ‘ being shiite’ , ‘ Karbala Mohr’, calling women, sisters’ , showing sympathy, sacrifice and finally martyrdom. These religious statements are exactly similar to Islamic revolution statements one of which emphasizes the truthfulness of Iranians’ defending the ideals of Islamic revolution. Both these discourse statements which are directly related to discourse statements of Islamic republic in which holy defense is emphasized as a means of defending the country, women(Namoos, by using the word’ sister’ for calling all women), and religion ( mentioning Karbala).

In this paragraph, the situation is formed by social order. According to this order, the captive has to obey the soldier, and the soldier has to obey his commander. In the meanwhile, both are in the helpless situation. In this order, both have the same idea, but the only difference is that the captive expresses his belief and loses his freedom, but the soldier does not. So, he has more freedom, although he is also a kind of captive in a sense. The captive and the guard are alike, because both are fighting for their countries. The climax of this order is the time when the guard says if he is ordered to kill his religious brother, he will kill his commander and then himself.

The inter-textual situation clearly shows the interaction between the people who are involved in this scene: Habib wants to say his prayers, the guard puts the gun aside and gives him a Mohr, Habib does not trust him, as he is a stranger, the guard calls the woman ’sister’, he says the Mohr is from Karbala, and then he indicates that he is a Shiite. The lines below show this interaction more clearly:

‘’Give it, sister / This Mohr is from Karbala / Like you / But I am a soldier now / I decided… to reach Iranian troops.’’

In fact, the guard is to make an interaction with a captive and attract his trust in an incredulous atmosphere. Therefore, all these statements of different kinds are to create a social order. Wile, if there had not been any statements, neither social order nor interaction would have been produced.

Explication level

Interpretation level corrects our understanding that discourse participants are independent, and obviously indicates that discourse action depends on non-explicated interior elements-common sense extracted from contextual knowledge. In other words, interpretation only explains the dependence of discourse action on presupposition extracted from contextual knowledge. It can not analyze the relationships of power relations and the ideologies inside with discourse action. Explication level is needed now. The analysis of women’s memories of Iran –Iraq war showed that discourse doers are not independent and are affected by official Islamic republic, Islamic revolution, and religious discourses which are of our concern in this research. They are formed by the guidance of presuppositions stem from common sense based on contextual knowledge.

3-2-4- Data analysis and the results

1- This article has tried to analyze and show that narrations- women’s memories of war- are affected by time, place, and paradigm atmosphere surrounding it.

2– Based on the theoretic frame work of discourse critical analysis of Norman Fairclough from one hand and text analysis with its three critical aspects as description, interpretation, and explication, we arrived at sub-discourse as part of official discourse of Islamic republic and the reproduction of the statements of this kind of discourse. In fact, all extracted semantic statements from analyzed memories showed that they have affected by official Islamic republic discourse.

In case the narrations had been produced and analyzed out side this paradigm atmosphere, we would have come to the same discourse statements stem from the same atmosphere, and our narrations of war sub-discourse would have been different from what have already been reproduced.

3 - Another result of discourse critical analysis of the memories is to accept any change in the atmosphere of the dominant paradigmic discourse will change the narrations. We will not be worried whenever we hear a narration out side dominant paradigmic atmosphere. In fact, this article helps us speak scientifically about the accuracy of the narrations on war, and make the statements develop, because no narration-due to the abundance of languages- can completely explain all the dimensions of an incident. Different versions of an incident are only able to narrate that incident accurately.

4 – The effect of official discourse of Islamic republic is clearly obvious in these memories. Women’s memories of Iran- Iraq war are expressed by the same official statements such as ‘segregation of men and women’, ‘paying attention to personal distance between men and women’, ‘rightfulness of Iran’s troops’.

5 – Detecting ideological elements of contextual knowledge implied in official Islamic republic discourse.

6 – Detecting elements and statements of official discourse in women’s memories based on women’s understandings of themselves and war.

7 – Power relations in the body of Islamic republic and its official discourse forms the women’s narration of war based on their knowledge of war as a social phenomenon.

8 – The connection between official discourse of Islamic republic with the statements of religious discourse and Islamic revolution discourse and also their penetration into profound layers of women’s beliefs have justified women’s styles of narrations. This is another out come of this research.

References:

1 – Smart, Berry, 2006, Michael Foucault, translator, Leila Jo afshani and Hasan Chavoshian, Akhtaran Publication.

2 -Bahrampoor, Shabanali; 1999, An introduction to discourse analysis, a collection of articles; Discourse analysis by Mohamadreza Tajik, Fahang Goftman Publication.

3-Raeesi, Reza, 1993, Captive 0339, Memories of Khadijeh Mirshekar, Hozeh Honari, Islamic Propaganda Organization.

4- Salimi, Asghar; 2004; Discourse in the thinking of Foucault; Kayhan Farhangi magazine, 219 Tehran, Kayhan Institution.

5 – Sheikh, Mohamad Ali, 1984, a research in the thing of EbN Khaldoon, Beheshti University Publication.

6 – Fairclough, Norman, 2000, Discourse critical analysis, a group of translators, Tehran, Media research and study centre.

7 – Mir Fakhraee, Tezha, 2004, Discourse analysis Process, Media research and study centre.

Fariba Nazari, M.A. in Sociology,

Islamic Azad University-Central Branch of Tehran

frbnazari@yahoo.com

Number of Visits: 4698

The latest

Most visited

- Commander of 19th Fajr Division

- The Account of the Injury of Hassan Ghabeli Ala’a

- Material Intellectual Property Rights of Oral History Work-9

- Da (Mother) 94

- Blood Sharer

- Da (Mother) 95

- The Oral History Association is not allowed to interfere legally in the issues of this field

- “Internal Reaction” published

A section of the memories of a freed Iranian prisoner; Mohsen Bakhshi

Programs of New Year HolidaysWithout blooming, without flowers, without greenery and without a table for Haft-sin , another spring has been arrived. Spring came to the camp without bringing freshness and the first days of New Year began in this camp. We were unaware of the plans that old friends had in this camp when Eid (New Year) came.

Attack on Halabcheh narrated

With wet saliva, we are having the lunch which that loving Isfahani man gave us from the back of his van when he said goodbye in the city entrance. Adaspolo [lentils with rice] with yoghurt! We were just started having it when the plane dives, we go down and shelter behind the runnel, and a few moments later, when the plane raises up, we also raise our heads, and while eating, we see the high sides ...The Arab People Committee

Another event that happened in Khuzestan Province and I followed up was the Arab People Committee. One day, we were informed that the Arabs had set up a committee special for themselves. At that time, I had less information about the Arab People , but knew well that dividing the people into Arab and non-Arab was a harmful measure.Kak-e Khak

The book “Kak-e Khak” is the narration of Mohammad Reza Ahmadi (Haj Habib), a commander in Kurdistan fronts. It has been published by Sarv-e Sorkh Publications in 500 copies in spring of 1400 (2022) and in 574 pages. Fatemeh Ghanbari has edited the book and the interview was conducted with the cooperation of Hossein Zahmatkesh.